An Abundance Of Bias: New COVID School Closures Book Rewrites History

By Wendy Orent Published 5/29/25

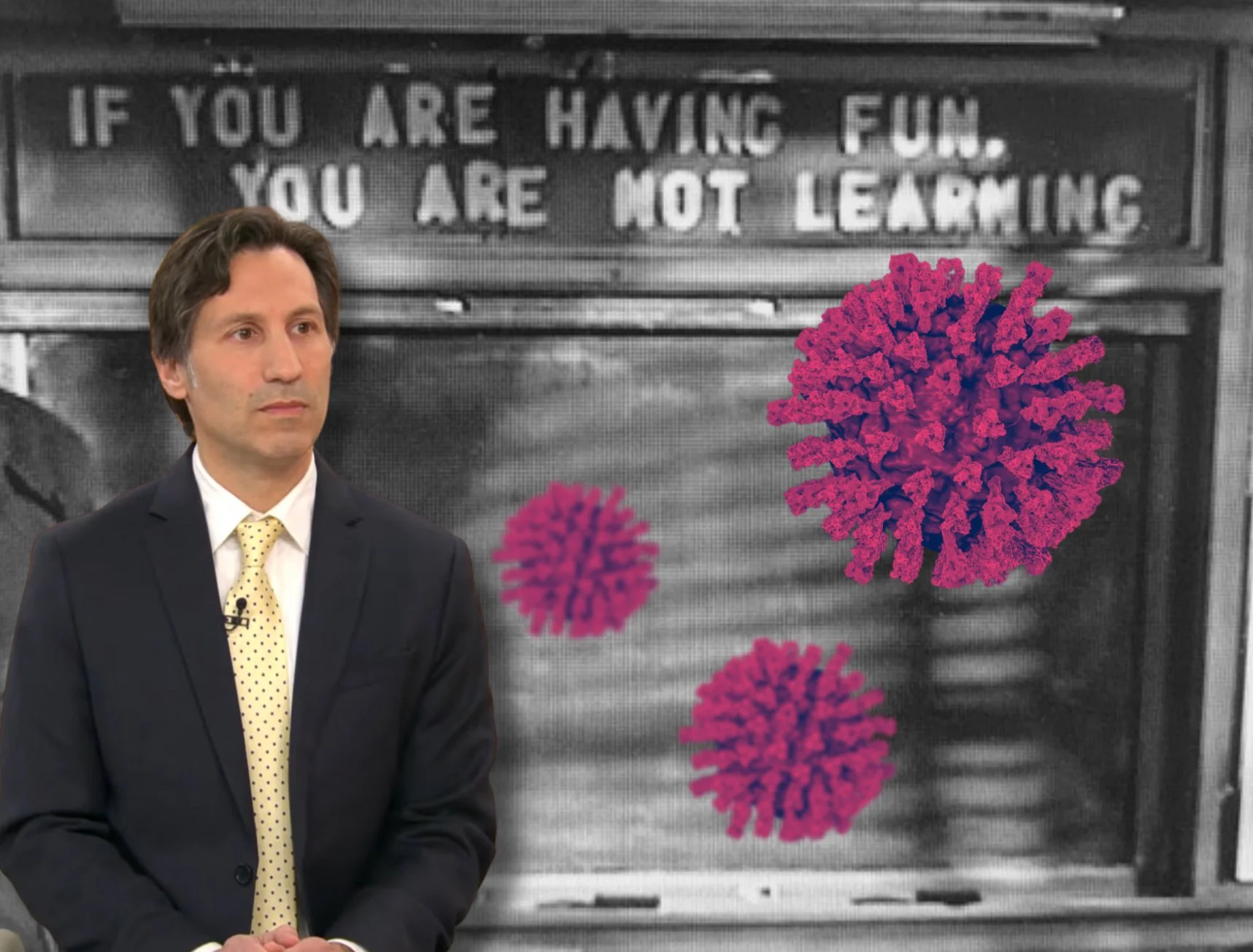

“I love research,” David Zweig says in the introduction to An Abundance of Caution: American Schools, the Virus, and a Story of Bad Decisions.” That love isn’t evident in his book. At a time when the so-called “legacy media” are chastised for trying for too much balance, for struggling to maintain an appearance of even-handedness, Zweig discards any pretense to objectivity. He detests school closings, so much so he’s devoted an entire book to it. This long and highly repetitive text ranges in tone from apparently sober discussion to a protracted wail. But evidence-free, light on statistics, absent any other viewpoints, and not infrequently wrong, all his arguments amount to the same thing: Zweig is angry that schools closed during the early months of the pandemic. And he wants to make sure you know it.

Let’s review the case for a moment. In late 2019, rumors of a new, transmissible, human-adapted, virulent disease spreading in the vast megalopolis of Wuhan, China, began to circulate worldwide, followed shortly by the disease itself. By January 23rd, Wuhan had locked completely down, but it was already too late. The disease sped to northern Italy, where many Chinese workers were employed in clothing factories, and people, mostly elderly, began to die in frightening numbers. The U.S. wasn’t far behind: on January 18th, doctors took a sample from the first case to be laboratory-confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Shortly afterward, cases sprang up elsewhere in the country.

By March 12th, the nation had shut down. School closings, a patchwork system controlled at the state and even the school district level, went into effect, with some indignation by certain, often-privileged parents, but with a general acceptance that we needed to “slow the spread” of the disease across the country. After a few weeks, most schools shifted to on-line or hybrid learning, where children either studied remotely on school-provided Chrome laptops, or, eventually, started to attend classes again, though infrequently, and surrounded by great wells of space – sometimes 44 feet around each child, sometimes a mandated six-foot distance from their fellows.

Nobody liked these systems, and aside from some highly scholastic and introverted kids who flourished, most children began to slip behind, academically and socially. To be stuck behind a flickering gray laptop hour after hour, working on tedious or incomprehensible assignments, listening to teachers droning on and on through a distant screen, distressed and frustrated most children, and caused academic delays that many researchers have noted and tracked.

But what infuriates Zweig is that he thinks schools shouldn’t have been locked down in the first place, since other countries (read: European countries, mostly unnamed) didn’t lock down at all, and anyway lockdowns were pointless even from the beginning. How do we know? Because the arguments were based on models. The very notion of models has a strange effect on Zweig: garbage in, garbage out, he intones, and he makes sure we know that all these models were wrong. They were based, for one thing, on pandemic influenza, which is all the modelers had to go on, as the 2003 outbreak of a related coronavirus, SARS-CoV-1 behaved in an entirely different fashion from Covid: it spread sluggishly, late in the course of infection, and generally in hospital settings. But pandemic influenza is also not a perfect model for Covid. Unlike Covid, flu is often spread by surface contamination. Basing Covid response on influenza led to hygiene theater: the scrupulous hand-washing and sanitizing; the meticulous scrubbing of food packages; the disinfection of surfaces, including (when the lockdowns partially lifted) shopping carts. None of it mattered much. Covid’s chief manner of spread is airborne, as several aerosol scientists (including Kimberly Prather, an atmospheric chemist Zweig holds up to particular scorn, though it isn’t clear why), demonstrated quite early on.

Still, the “experts” had to work with what they knew, and what they knew was influenza. At first, no one seemed to think the new disease could be worse than influenza, which, after all, has killed up to 80,000 Americans, mostly elderly, in recent years, according to the CDC. And no one knew if schools were going to drive transmission rates or not. Certainly, children in school settings sometimes drive influenza outbreaks. So, in “an abundance of caution,” state and local governments shut the schools down.

That decision enrages Zweig, who argues that influenza kills more children than Covid, but when you look at the actual figures you wonder what he’s smoking. According to Jonathan Howard, physician and author of We Want Them Infected, some 450 children had died of Covid by May of 2021. Zweig claims that in several given years, influenza claimed far more. For instance, according to Zweig, in the year 2012-2013 the CDC attributed 1160 children’s deaths to the flu. This contradicts the CDC’s report itself, which listed pediatric influenza deaths as “more than 170.” According to the American Hospital Association the highest pediatric death toll ever recorded was the year 2009-2010, when the novel Swine Flu pandemic took 288 children’s lives. Zweig’s “love of research” has failed him here. Is this carelessness, or inventiveness? There’s no way to know.

At a time when the so-called “legacy media” are chastised for trying for too much balance, for struggling to maintain an appearance of even-handedness, Zweig discards any pretense to objectivity.

A principal reason for shutting schools down is something Zweig barely seems to recognize, even five years into the pandemic. Unlike flu, which spreads only weakly if at all from presymptomatic people, Covid has, and retains, the terrifying ability to spread virulent disease even though the transmitters have no symptoms. Covid shares this ability only with polio, pneumonic plague, and, perhaps, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) though that asymptomatic spread is apparent mostly with the intense exposure in households. Symptomless spread is Covid’s secret sauce. It’s what makes the disease uncontrollable without masks and vaccination, and it helped the decision to shut schools down, because telling children, teachers, and staff merely to stay home when sick would not prevent contagion from spreading.

When he recounts the horror of distanced hybrid schooling, the valiant if not-altogether-successful attempt to bring kids back to the classroom on a part-time basis, separated from each other by at least six feet, Zweig has particular fun hashing out the mysteries of the six-foot rule. He calls it “the ill-considered fetishization of an arbitrary metric” for which, he assures us, there is no evidentiary basis whatsoever.

On that, he’s wrong. There is a basis for the six-foot rule. The careful experiments of Richard Strong and Oscar Teague, two distinguished American plague researchers who went to Manchuria during the 1910 pneumonic plague epidemic, showed that the plague germ, Yersinia pestis, remained infectious in droplets taken from coughing patients six feet away, and no further. When you’re dealing with an airborne virus like Covid or measles, though, the six-foot rule no longer holds, since many of these viral particles remain aloft and move for longer distances. The World Health Organization initially assumed that Covid spread in large particles called droplets, which don’t disseminate much further than six feet. It took years for the WHO to acknowledge that, indeed, Covid is airborne, and that, therefore six feet of distance affords you no real protection.

It's probably safe, therefore, to say that we could have dispensed with the one-way traffic signs directing people how to move in grocery stores, or the six-feet apart green plaques on the floor. What people, including children, needed to safely conduct their lives were masks, good-quality masks, which originated during that same Manchurian plague pandemic of 1910. The originator of the N-95 mask, a Chinese-Malaysian, Cambridge-trained physician named Dr. Wu Lien-teh, insisted that physicians and attendants working in the pneumonic plague wards always wear one of his layered-gauze devices. His masks saved lives; their descendants do so today.

Yet Zweig makes his contempt for masks clear. He cites the Dean of the Yale School of Public Health, emergency room physician and “Covid pundit extraordinare” Dr. Megan Ranney (another woman, like Prather, he particularly despises), tweeting to “her tens of thousands of followers impassioned calls for student mask mandates, dismissing those who had concerns about them by saying ‘masks aren’t harmful,’ ‘masks hurt no one,’ and ‘masks literally cause zero harm.’ But many parents rightfully felt that a piece of material strapped to a six-year-old’s face for eight hours a day, every school day for more than a year was, indeed, a clear form of harm.”

But Zweig never tells you what that harm was, except for vague mutterings about how hearing-impaired children might have struggled to learn while their teachers wore masks.

One reason Zweig has no patience for masks or school shutdowns is that he has never taken Covid seriously. In one of his more shocking passages he tells you why. He doesn’t know anybody who died of Covid, and he suspects many of his readers don’t either. That passage alone gives the game away; despite his dutiful complaints about the deaths of essential workers, Zweig really doesn’t care. Covid is something that happens to other people, the kind of people who don’t live where we live. Covid doesn’t affect Zweig’s life personally – only the restrictions do, so it’s only the restrictions he cares about.

That some modelers initially predicted that without mitigations four million Americans would die (about eight times the number who died in the 1918 flu pandemic) impresses him not at all. Projections more to Zweig’s liking, since he lionizes the people who developed them, were far more modest: deaths in the range of 20,000 to 100,000. Stanford health economist Jay Bhattacharya, now head of the National Institutes of Health, predicted in Wall Street Journal op-ed that, although some modelers claimed that 4 million Americans could die of Covid, he believed the true figure would be closer to 20-40,000. But though Bhattacharya (“a true mensch,” in Zweig’s words), and fellow Stanford scientist Dr. John Ioannides weren’t using the kind of models Zweig despises, their predictions were still off by orders of magnitude. Some one and a quarter million Americans have died of Covid as of this writing, and the death toll, five years and several vaccines later, remains around 300 per week.

One reason Zweig has no patience for masks or school shutdowns is that he has never taken Covid seriously.

As for children, whom Zweig considers almost immune, 2000 American children have died anyway – and that’s with mitigations: the hybrid schools, the abandoned school cafeterias, the silent lunches, the coldly-flickering remotes, the cloth or surgical or N-95 masks (which don’t work anyway, Zweig assures us, on the basis of nothing – or no evidence that he presents). Zweig undercounts and dismisses many of these deaths - many kids died with Covid, not of it, he explains – but that the death toll might have been much higher without mitigations in place he does not mention, perhaps because he doesn’t believe it. That, as of December 2023, 17,400 children worldwide had died of Covid, according to UNICEF, fazes him not at all.

Zweig makes school lockdowns an American story and an American tragedy. That dozens of countries imposed more stringent and longer-lasting shutdowns doesn’t merit mention in his book. According to the Institute for Greater Europe, “Globally, full and partial school closures stretched for an average of 224 days with low-income countries prolonging their closures. As a result of this sudden disruption, education was changed dramatically – with the distinctive rise of e-Learning, where teaching was now undertaken remotely on platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Classroom.”

As for Sweden – Zweig loves Sweden, though his version of Sweden is an entirely mythical country – lockdowns happened there too. The IGE reports that despite Sweden’s efforts not to lock down, in the hope that mass infection, ripping through the young and healthy, would achieve herd immunity, the country ended shuttering schools anyway: “The impact of school closures as a result of these lockdowns proved to be the worst on record in Europe.”

Zweig scorns teachers and teachers’ unions (he reserves Megan Ranney- and Kimberly Prather-level vituperation for Union President Randi Weingarten), because by opposing opening schools they refuse the noble “call to service” that teachers should heed. That, according to Education Week, over 1000 teachers died of Covid between 2020-2022 isn’t something that Zweig, safe behind his laptop in his suburban home, seems to recognize. Zweig shares the view of Jay Bhattacharya and the other writers and signatories of the so-called Great Barrington Declaration (Zweig was present at the signing) that anyone younger than seventy is grist for the Covid mill, including teachers: if masses of people, including teachers and schoolchildren, contract Covid, that protects the vulnerable among us and brings the pandemic to an end. Infecting schools is much better than closing them.

Now we come to the oddest point of all, which reveals to the thoughtful reader exactly what sort of chronicler Zweig is. The book ends in 2022. Now, why is that significant? Zweig ends his reportage while ignoring the evolution of two major variants: Delta, and Omicron. Both of these variants caused fresh infections even among people with full immunity, through vaccination or prior infection, to earlier strains. Viruses that are as relatively unstable as the RNA virus SARS-CoV-2 will evolve to escape existing immunity. From an evolutionary stand point this development was entirely predictable.

But the story doesn’t end there. Since the population who had been the principal targets of the infection, people older than 65, were also those most heavily vaccinated, the virus’s chief prey had been, as it were, taken off its table. The new strains evolved to be at once more transmissible and better at infecting children, apparently because they infected cells higher up in the airways, in the nasal passages, where children are more vulnerable to infections.

Infecting schools is much better than closing them.

Children caught Omicron in far greater numbers than they had the ancestral strains. The death toll mounted from 450 to around 2000. Many of these children had co-morbidities like obesity or diabetes, but not all. Schools, even in closing-recalcitrant states like Florida, began shuttering, because there weren’t enough students or staff to attend. Omicron represented a fresh wave of horror: less severe than Delta, it still killed many thousands, despite Jay Bhattacharya’s close associate Marty Makary, now director of the FDA, fallaciously and foolishly calling it “Omicold.” It is no cold. 300 people are still dying of Covid every week in the USA alone, and they’re dying of Omicron.

It is quite remarkable that Zweig, writing an indignant history of Covid-induced school closings in America, chooses to utterly ignore the most child-hungry variants of all, Omicron and all its descendants. The word Omicron does not appear in the entire 464-page book.

Zweig ends his book with a lament for the years of lost childhood, lost to school closings, fanaticism, masks, flickering screens, six-foot rules, forced isolation, forced inactivity. No one will say these were happy years for the world’s children. But children are resilient, a term Zweig hates. He doesn’t believe it. He thinks the harms are permanent, that the damage will follow these injured children forever.

To prove it, he interrogates his son. In Zweig’s own words (but with my emphasis): “In spring 2023 I asked my son, who was finishing sixth grade, something about fourth grade and his year of hybrid and school closures. At first he said he had forgotten most of the particulars I had mentioned to him about remote learning. He marveled for a moment at his memory lapse. And then, as a vague wash of details and feelings came back to him about the frustrations, the unique and unfamiliar loneliness, and the profound, agonizing boredom, he paused for a long moment then shook his head. ‘Wow,’ he said. “I forgot how much that sucked.”